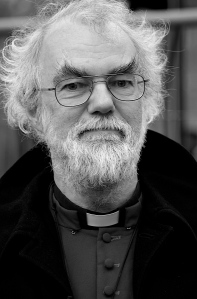

As a Catholic and an Englishman I have never quite understood the enthusiasm of some of my European co-religionists for the idea that there must be strict separation between state and Church, and have often thought that the amusement to be derived from watching indignant Frenchmen flail their arms around indignantly about Bishops sitting in the House of Lords is itself ample justification for maintaining the politico-ecclesiastical status quo. But then I read the latest contribution of Dr. Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, to public debate…

As a Catholic and an Englishman I have never quite understood the enthusiasm of some of my European co-religionists for the idea that there must be strict separation between state and Church, and have often thought that the amusement to be derived from watching indignant Frenchmen flail their arms around indignantly about Bishops sitting in the House of Lords is itself ample justification for maintaining the politico-ecclesiastical status quo. But then I read the latest contribution of Dr. Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, to public debate…

The contents of his critique of the Coalition now governing the U.K. are by now well known. As interesting as the piece itself were the comments posted by readers under various news reports. Comments at the Telegraph – aside from one comparing the erstwhile cleric to Oscar Romero – were predictably scathing: ‘Another diatribe from the Guardian/BBC Cleric’ opined one wit. ‘More leftist drivel from another Archbishop of Canterbury’, fumed another.

Meanwhile, talking heads at the Guardian were in a quandary over whether to give way to an instinct that applauds any criticism of the odious Tories, or to wring their hands over Christians meddling in politics. ‘What a pity Williams is such a wuss when it comes to standing up to the homophobic bigots in his own organisation’, moaned one commentator. ‘Well done Rowan! We paid for Bankers bonuses, and then we get our services and NHS cut. Not just the Nasty but the Nastiest and Greediest party’, raged a presumably oppressed worker who had managed to find time in his busy schedule to browse the Guardian online.

In strikes me that there are three broad categories of political issues upon which religious leaders voice opinions, ranging from morally obligatory and helpful interventions at one end, to pointless and divisive, at the other.

In the first category are issues regarding which there can be only one morally correct course of action, such as abortion and euthanasia. The moral norm prohibiting the direct killing of the innocent means that the only morally good response to such practices is to forbid them entirely. There can be no legitimate disagreement about either the principles or their application to concrete cases. Also included would be important issues concerning the correct use of human sexuality and respect for human rights – including, for example, the right of workers to a just wage. On all such issues, interventions from clerics are not only welcome, but even a duty on their part. Far from being meddlesome and hindering the democratic process, they aid democracy by recalling us to timeless moral principles without respect for which there will be great suffering, moral ruin for individuals, and decay of societies.

In the second category are issues involving absolute moral principles, but whose application to concrete circumstances is complex, and about which there can be legitimate disagreement. An example might be a decision about whether or not to go to war. According to classical ‘just war’ theory, there are certain criteria which must be fulfilled for warfare to be morally justifiable. Because of the difficulty in applying these principles to highly complex situations, and the fact that very few individuals will have access to the sensitive information which might be necessary to form a fully informed judgment, it is likely that even those who agree wholeheartedly about the principles in question may disagree about the justice of a particular war. Regardless of this, religious leaders will perform a laudable public service – particularly in an age when military decisions can be made by unscrupulous politicians based on purely utilitarian considerations – by calling for respect of the principles of necessity, proportionality, discrimination, and so on, which ultimately aim at protecting the human dignity of individuals in a brutal situation. They may also do a service to consciences by giving their opinion on the justice of a particular war, though there is the possibility of error.

In the second category are issues involving absolute moral principles, but whose application to concrete circumstances is complex, and about which there can be legitimate disagreement. An example might be a decision about whether or not to go to war. According to classical ‘just war’ theory, there are certain criteria which must be fulfilled for warfare to be morally justifiable. Because of the difficulty in applying these principles to highly complex situations, and the fact that very few individuals will have access to the sensitive information which might be necessary to form a fully informed judgment, it is likely that even those who agree wholeheartedly about the principles in question may disagree about the justice of a particular war. Regardless of this, religious leaders will perform a laudable public service – particularly in an age when military decisions can be made by unscrupulous politicians based on purely utilitarian considerations – by calling for respect of the principles of necessity, proportionality, discrimination, and so on, which ultimately aim at protecting the human dignity of individuals in a brutal situation. They may also do a service to consciences by giving their opinion on the justice of a particular war, though there is the possibility of error.

Then we come to the kind of issues Dr. Williams has been dealing with in his recent intervention, such as policies on health, education, and social security. As it happens I agree with at least some of Williams’ criticisms, but this is beside the point. Providing very general principles (which are conceded by all political parties in the UK anyway) are respected, there are a myriad of different ways in which good people who care about the poor and the sick might think the benefits system or the NHS ought to be organised for the welfare of those concerned. For clerics to weigh in heavily on one side is – as the comments above show – needlessly divisive and, in the event that they are proved wrong, diminishes the prestige of their spiritual office. Without making concessions to the relativism of the present age, the clergy must surely seek to be ‘all things to all men’, and not cut themselves off from those who differ from them in matters regarding which there can be legitimate differences of opinion.

‘Archbishop Cranmer’, in his blog, praises Dr. Williams for braving the ire of those who think the public square ought to be scrubbed of religion. I disagree, for by entering the public square disguised as a political commentator, Dr. Williams has implicitly sided with those who wish to eradicate religion from public life. It is of course true that religion is not simply a private good for individuals, but a public good, and that healthy and prosperous societies are generally those in which religion, regardless of whether it be officially established or not, is a part of the social fabric of the nation, and plays an important role in giving orientation to public debates. This is why it is important that religious leaders should not be afraid to speak out on important issues in public. But when they do, they must speak as religious leaders, not as ‘op-ed’ pundits. They must recall to the mind of a materialistic and amoral society the eternal truths of religion and the timeless principles of the moral law, and not become involved in petty squabbles about the organisation of the benefits system, or whether or not the NHS should be run by consortia of GPs. For, if religious leaders busy themselves playing politics, who will undertake the much more important job of preaching religious truths… the politicians? I think not.

Related Posts:

- Freedom of Religion and the Limits of Secularism

- Will the Pope Make Britain Sit Up and Think?

- Christianity, the Crucifix, and European Values

(photo of Rowan Williams: © Steve Punter; photo of Westminster Abbey: Gail J. Cohen. No endorsement implied)

Posted on June 13, 2011

0